I had a conversation recently with a friend of mine who was entreating me to take the subway downtown so that we could have a proper night out. I was stuck between the decision of driving, therefore cutting down the travel time by half, but limiting my alcohol intake (and thus the severity of a subsequent hangover); or taking the TTC so I could quaff indiscriminately (after a later arrival, of course).

I had a conversation recently with a friend of mine who was entreating me to take the subway downtown so that we could have a proper night out. I was stuck between the decision of driving, therefore cutting down the travel time by half, but limiting my alcohol intake (and thus the severity of a subsequent hangover); or taking the TTC so I could quaff indiscriminately (after a later arrival, of course).But the time and the drinking did not factor into the decision making process. My major concern was the feminist idea of the male gaze, identified in movies and magazines, but also observable in any public area.

In general, I find that I can blend into the masses of people on a streetcar or on the subway in the day. People are reading or chatting or listening to music. I am often doing the same. But taking public transit at night as a single female is a slightly different experience. One becomes very aware of the male gaze and all the complex power realationships that it involves.

In general, I find that I can blend into the masses of people on a streetcar or on the subway in the day. People are reading or chatting or listening to music. I am often doing the same. But taking public transit at night as a single female is a slightly different experience. One becomes very aware of the male gaze and all the complex power realationships that it involves. In her Saturday column in the Globe, Karen von Hahn touches on the male gaze and its relation to the niqab (a type of veil worn by Muslim women), after British Cabinet minister Jack Straw stated that the veil is a "visible statement of separation and of difference" and asked women visiting his doctor’s office to consider removing it. Von Hahn asserts that the niqab makes a “fashion statement” beyond its original religious purpose based on its colour and the degree to which it conceals the body.

In her Saturday column in the Globe, Karen von Hahn touches on the male gaze and its relation to the niqab (a type of veil worn by Muslim women), after British Cabinet minister Jack Straw stated that the veil is a "visible statement of separation and of difference" and asked women visiting his doctor’s office to consider removing it. Von Hahn asserts that the niqab makes a “fashion statement” beyond its original religious purpose based on its colour and the degree to which it conceals the body. However, Straw’s comment about "visual statements of separation and difference" can be applied to myriad styles of dressing, and not just religiously based ones. Goth-style dressing is the first statement of separation and difference that comes to mind; so does the punk style or any kind of anti-establishment fashion movement based in politics. And more often than not, these styles are mainly worn by teenagers who are going through a stage in life where they are questioning authority and attempting to find their place in society.

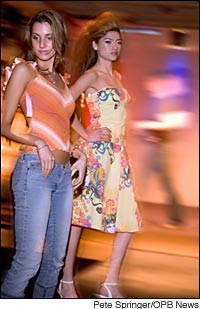

However, Straw’s comment about "visual statements of separation and difference" can be applied to myriad styles of dressing, and not just religiously based ones. Goth-style dressing is the first statement of separation and difference that comes to mind; so does the punk style or any kind of anti-establishment fashion movement based in politics. And more often than not, these styles are mainly worn by teenagers who are going through a stage in life where they are questioning authority and attempting to find their place in society.I’m a little less political in my dress. When I “blend in” on the TTC, it is often because of several “fashion” factors: I wear jeans, a ubiquitous dress item; I usually wear sunglasses, concealing my eyes from any chance of eye contact with others; and I often listen to my iPod, the earphones making the loudest (ironically) statement that I do not want to engage in any social contact. I send out strong signals that I don’t want to be looked at or participate in any kind of interaction.

This becomes more difficult when my demeanour says something different when on my way out to a social event. I have no sunglasses (usually it is nighttime), no iPod (don’t want to risk losing it) and the jeans have been traded in for a slightly more “polished” outfit (this is when the H&M impulse buys make their debuts). While this style of dressing is completely appropriate for a social event with my peers, it facilitates the unwanted male gaze on the transit system. Hence my reluctance in the aforementioned conversation with my friend.

This becomes more difficult when my demeanour says something different when on my way out to a social event. I have no sunglasses (usually it is nighttime), no iPod (don’t want to risk losing it) and the jeans have been traded in for a slightly more “polished” outfit (this is when the H&M impulse buys make their debuts). While this style of dressing is completely appropriate for a social event with my peers, it facilitates the unwanted male gaze on the transit system. Hence my reluctance in the aforementioned conversation with my friend.So can we blame the Muslim women that von Hahn references in her column who “claim relief from the oppression of the male gaze”? Do the various Muslim headdresses allow women to “blend in” as my daytime uniform on the TTC does? Or do we see any piece of clothing as a “continual manifestation of intimate thoughts, a language, a symbol” as von Hahn quotes Balzac in her piece?

You can’t escape where symbols originate from or the process of how they come to mean something. But this is where knowledge and freewill come into play. If Muslim women are given the choice to wear a headdress, and they choose to do so, that is their prerogative. If wearing a niqab or burqa makes them feel less conspicuous and more comfortable, then why shouldn’t they wear it? I see a problem arising when women are not given the choice, or when a politician interprets a "fashion statement" with limited knowledge of the full symbolism and function.

So what was my travel decision for my social engagement that night? I made a "visible statement of separation and of difference" by driving my car, my entire body hidden inside my car and my face somewhat obscured by the reflection of streetlights on the dashboard. I felt comfortable, I felt safe. And I felt a hell of a lot better the next morning for the modest amount of alcohol I drank.

1 comment:

great article steph! it does seem strange to only ask women wearing a burqa to remove it - does this minister ask priests to remove their collar or monks to remove their robes? why are only muslim symbols of 'separation and difference' targeted? what is with this us vs you mentality? and while it may be so that these women don't truly have the same freedom of choice as other women might, picking on particular clothing choices seems like a prioritizing disaster. if they are so worried about the isolation of women, how about putting that energy into attacking spousal abuse (across all ethnicities)?

Post a Comment